Fungus Simulation

17 Jan 2021The Motivation

Since I learned rust, I always want to use it more. But outside of Advent of Code, I usually don’t have an excuse.

A few months ago I came across an article about fungus spore simulation (or something). They’d used this simulation to create these cool pictures, and it sparked my interest. It reminded me of the sort of stuff I used to do on this blog.

So I had a crack at implementing it myself - without looking at their code, just based on the descrition of how it worked. I knocked something together in an afternoon, and the results were… disappointing.

After Christmas, when I had a little more free time, I decided to have another crack at it - rewriting it more or less from scratch - and the results were much better. Clearly I did something wrong the first time around.

And now, because I didn’t take enough annual leave during the first lockdown, I have some more time off work, so here’s a write up…

The Concept

I called this a fungus simulation, I don’t know if that’s the right name for it. I can’t find that original article, and a google search only returns academic papers.

But the model itself is a lot like an ant colony simulation.

The way it works is, the agents (spores, ants) move around a grid, leaving behind a trail of ‘pheromone’. Other agents can sense this pheromone and use it to follow the same path.

In the ant colony, this is used as a sort of collective intelligence for finding food and bringing it home - i.e. one ant finds food, and other ant’s can follow it’s trail to get more of the food or find home.

In the case of this funcgus simulation, there is no food, no home. The spores move around more or less aimlessly, except for trying to find each other.

The Model

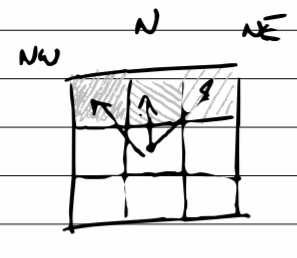

The spores move around on a square grid. For simplicity, the grid wraps around at the edges, making it a doughnut shaped universe (like pacman).

Each spore has a position and direction of facing. At each step, they look at the three squares ahead of them - so if it’s facing north, it would look at the squares north, north-east, and north-west.

The spore decides which square to move to randomly, weighted by the amount of pheromone in each of those squares - more pheromone, more likely to move to that square.

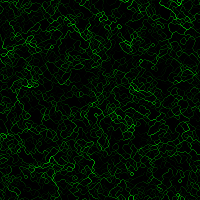

After moving, the spore leaves behind some pheromone in the square it just moved from. Over time, the phermone diffuses/evaporates, so if a spore leaves behind 100 pheromone, on the next ‘turn’ it might drop to 75, then 56.25, etc. depending on the diffusion rate.

Here’s an example of the spore trails from 5,000 spores, 0.9 diffusion rate, after 100 iterations

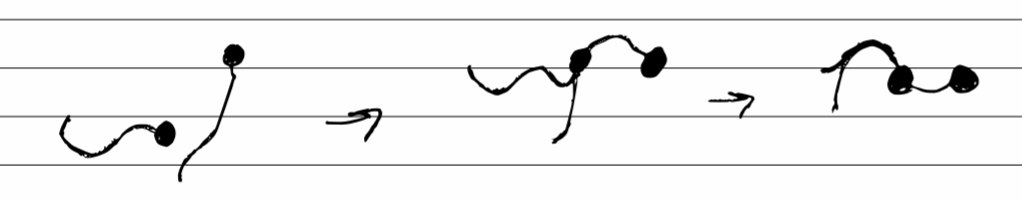

In addition, the spores have a ‘memory’ - a record of the N most recently visited squares. This is mostly meant to prevent the spores from getting stuck in a loop, following its own trail.

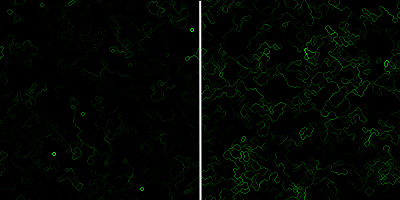

For example, compare these examples of zero memory (left) versus a memory of 10 (right)

Notice the no memory one has a lot of tight circles, while the long memory has more long, wiggly paths.

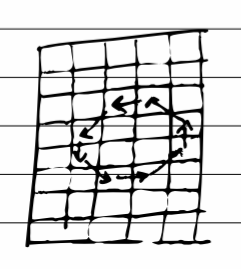

As you might expect, if you run the simulation long enough, the spores do eventually find each other, forming groups which are stuck in shared loops - the overall configuration becoming pretty stable.

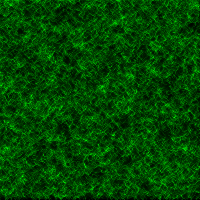

One other thing I added was the ability to have pheromone spread outwards to the 8 neighbouring squares - to diffuse - rather than just reducing/evapourating. To be honest, I don’t think the results are as interesting. It’s mostly a fuzzy blur (looks kind of like perlin noise?)

The CLI

You can see my code here. It has a CLI so you can play around, and generate your own images. There are lots of twiddly buttons for changing the behaviour, like the pheromone diffusion rate.

By the way, the animated gif was generated by using the cli to generate frames, then stitching them together with ffmpeg

$ fungus --iteration 1000 --every 1

$ ffmpeg -i output/fungus-%d.png fungus.gif

I’m not sure if the results are exactly what I had in mind from that original article - I seem to remember them being more ‘artsy’.

But it’ll do…

Chris.

[

]

]