Cooking for Software Engineers

04 Jan 2026The title is a reference to “Cooking for Engineers”, originally a blog post which spun off into a whole site. It re-imagines recipes as flowchart-like diagrams.

The writer of the original blog post jokes that actual engineers would probably hate the approach due to how imprecise it is - using estimated measurements, and timings based on senses (what it looks like, smells like, etc).

Well allow me to share an alternative, precise and (over)engineered approach to recipes

The Secret to Comedy*

I’d say I’m a ‘capable’ cook; I’m not skilled, but I can follow instructions.

Except, sometimes the instructions say things like “boil the rice… meanwhile”, and I’m not sure if I’m supposed to start the ‘meanwhile’ right away? Or, if I do that, will the sauce be ready too early? Or should I have already started?!

One solution to this is to plot everything out:

- How long will each step take?

- When does each step need to be completed (‘ready’)?

- Start at the end, and work backwards

Example:

- rice takes 20 mins

- stir fry takes 15 mins

- we want them ready at the same time

0 5 10 15 20

|---+---+---+---| rice

|---+---+---| stir fry

So, start the stir-fry 5 minutes after the rice. Easy.

This works for simple recipes with only a couple of things going on at once, where most of the things are ‘hands-off’ (like boiling rice), and where everything is combined at the end.

When that isn’t the case, we need a more complicated process. It breaks down into two stages:

- Dependency graph

- Timeline

Hot DAGs

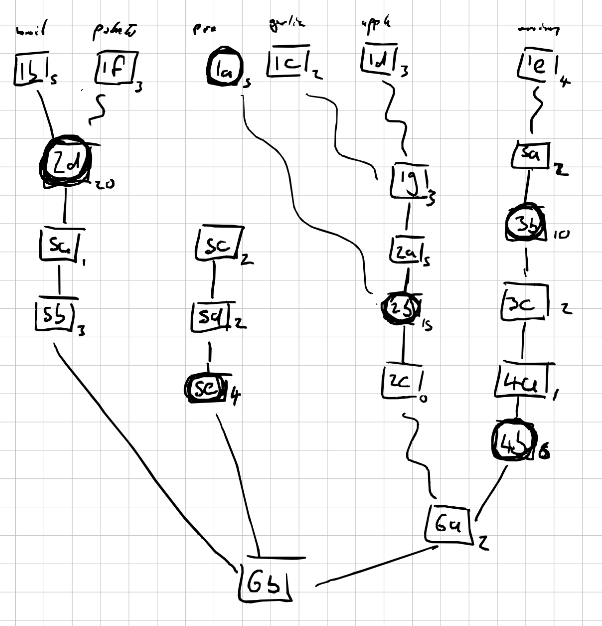

First, we have to break down the recipe into discrete steps, and arrange them into a dependency graph.

This means drawing a ‘node’ for each step, with an arrow between the step and any steps that depend on it - you have to break an egg before you can fry your omelette.

[crack egg] -> [whisk egg] -> [fry]

What we end up with is something like a flowchart; in technical terms it’s a ‘directed acyclic graph’ (DAG)

Here I’ve labelled nodes with step numbers; you can also use words. I didn’t draw arrows on the lines because I’m lazy (it’s read top-down).

The point of the graph is, it makes it easier to keep things in the right order when we come to do the timeline.

At this point, I also

- assign approximate times to each step

- identify whether the step is ‘hands on’ (square) or ‘hands off’ (round)

- draw a squiggly line for steps that can be prepared in advance

It’s important to account for the time that every step will take, whether that’s time roasting in the oven, time to chop an onion, or time to heat a drizzle of oil in a pan.

The mistake (one of the mistakes) I made in the past was not accounting for steps that aren’t explicitly timed; the recipe says to add the rice to boiling water and cook for 20 mins, but it doesn’t say how long it takes to bring a pan of water to the boil (it takes a while).

Some of the timing are likely to be different for different people. For example, it takes me a good 5 mins to thinly slice an onion (badly), while I imagine a skilled chef could do it in less than a minute.

Sliding Timeline

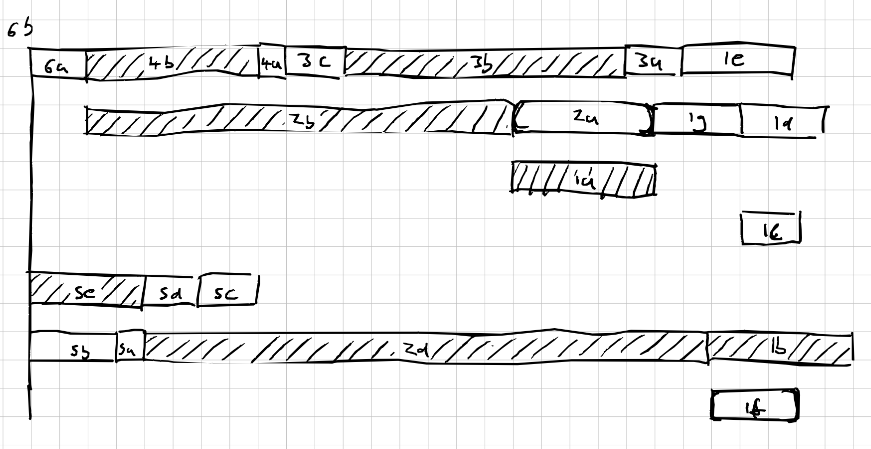

This starts out the same as the original, basic approach

- start at the last step(s) and work backwards

- draw a block for each step

- the block length represents how long the step takes

- blocks have to be placed behind any steps they depend on (per the DAG)

- indicate hands-off steps, e.g. with shading/colour

This first pass is likely to be ‘wrong’. In the above, we have multiple (independent) hands-on steps happening at the same time, such as 5c and 6a.

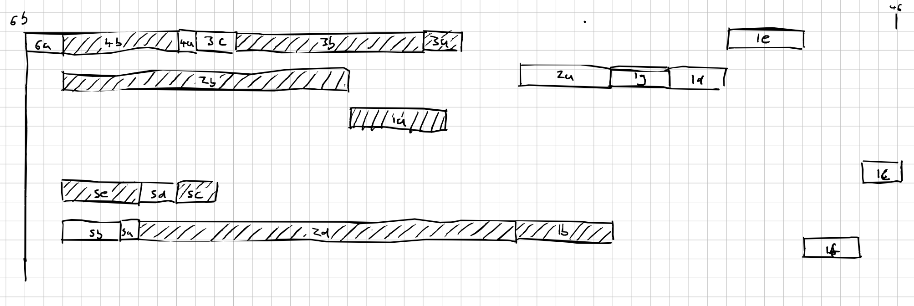

This is where the sliding comes in, and where it helps to use a tablet (or pencil and eraser)

For steps that can be prepared ahead of time, we can slide them as far away from their dependants as we want; an onion can be chopped the night before if need be. Steps which can’t (reasonably) be prepared ahead of time need to slide together with their dependants, e.g. heating oil and frying an egg in that oil.

Honestly, the sliding is not an exact science. To some extend, you just have to feel it out; play around with it until you get something that works/feels right

Here’s what I settled on for the above example

Once you have your timeline, you can rewrite the recipe in this new ordering, or timestamp the steps, or just work off the timeline diagram

(Note, since we start at the last step and work backwards, the timeline is read right-to-left.)

For Software Developers

The process I described is ‘fairly’ mechanical, so it seems natural to try and code it up.

You can see my attempt here - https://github.com/oatzy/recipe-optimiser

It… kind of works. It could be better. (Remember when I said it’s not an exact science)

For the input, we have to re-structure the recipe into json, with steps defined like

{

"id": "2b",

"duration": 15,

"hands_off": true,

"parents": [

"1a",

"2a"

],

"instruction": "Put meatballs in oven"

}

Here’s an example of what the script then generates

[ 0 - 3] ### (1d) Grate the apple

[ 3 - 6] ### (1f) Chop potatoes into chunks

[ 6 - 8] ## (1c) Peel and grate the garlic

[ 8 - 11] ### (1g) Combine ingredients for meatballs

[11 - 16] ##### (2a) Roll mince into evenly-sized balls

[11 - 16] XXXXX (1a) Pre-heat oven to 200

[14 - 19] XXXXX (1b) Bring a large saucepan of water to the boil

[16 - 31] XXXXXXXXXXXXXXX (2b) Put meatballs in oven

[18 - 22] #### (1e) Slice the red onion

[19 - 39] XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX (2d) Boil the Potatoes

[22 - 24] ## (3a) Heat oil in a large frying pan

[24 - 34] XXXXXXXXXX (3b) Add onions to pan, fry until golden

[31 - 32] # (2c) Remove from oven

[32 - 34] ## (5c) Heat oil in medium sauce pan

[34 - 36] ## (3c) Add balsamic vinegar and sugar, caramelise

[36 - 37] # (4a) Add wine stock, etc. to onions

[37 - 43] XXXXXX (4b) Bring to boil and simmer

[37 - 39] ## (5d) Add cabbage and stir fry

[39 - 40] # (5a) Drain potatoes

[40 - 43] ### (5b) Mash potatoes

[41 - 45] XXXX (5e) Cover, cook until tender

[43 - 45] ## (6a) Stir meatballs into gravy

[45 - 46] # (6b) Serve

(X are hands-off, # are hands-on)

Since recipes generally don’t have that many steps, an alternative approach might be to brute-force the ‘optimal’ recipe.

AI Interlude

As mentioned, the script requires converting the recipe into a particular JSON format. This can be a tedious process.

Then, it occurred to me that parsing prose into json is something an LLM might be good at.

To try this out, I wanted to use a local model. Problem is, my laptop doesn’t have a lot of RAM, so the only model I can run locally is a really small one.

Turns out a really small LLM takes a long time to do a bad job of parsing.

So I asked Gemini to help me improve the prompt, specifically for use with a small model - effectively asking an AI to dumb down the prompt for another, less intelligent AI.

It didn’t help.

And I don’t care enough to spend money on finding out if it works on a larger model, so… moving on.

When a Plan Comes Together

So having gone through all this planning, the whole cooking process runs smoothly now. Right?

The honest answer is: sometimes.

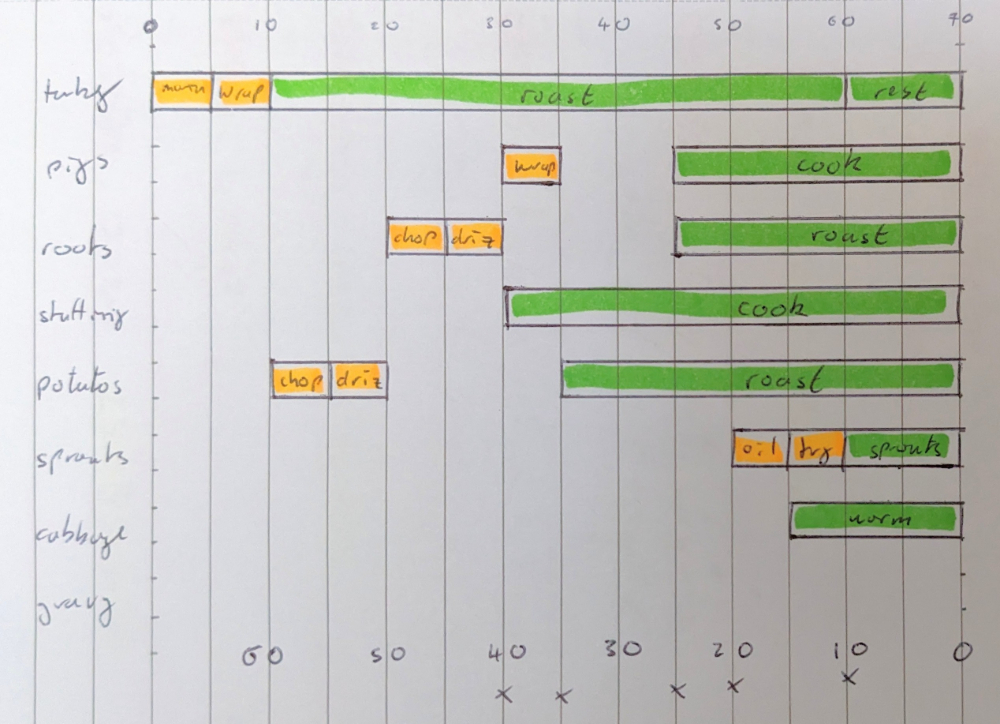

I actually used this approach when cooking Christmas dinner this year

And I have to say, it was pleasing to set a timer going and be able to say “at minute 5 do X, at minute 10 do Y”. A lot less stressful too.

It’s also good for identifying what you need to prepare ahead of time, and what you have time to do while other stuff is cooking.

But the “Cooking for Engineers” guy was on to something - with cooking, you can rarely be so precise.

For example, when a recipe says to fry on “medium high” heat, that’s not an exact setting. Besides which, there are natural variations in people’s equipment, some ovens run hotter than others. Plus, the ingredients may vary in size or shape in a way that subtly affects cooking time.

So sometime you do just have to rely on your senses, make adjustments on the fly, and not get so hung up on following the plan.

Even if you spent more time working out the plan than it took to cook the damn meal…

Chris

[the latest instalment in the “I started a new hobby and tried to solve it with maths” series]

*Timing