When a Random Sample is as Good as the Whole Thing

28 Oct 2022Background

At a high level, what we have is a Django-based server, with celery for running tasks.

A user submits a workflow, which is translated into a ‘canvas’ of tasks. The tasks are run in a celery worker, often on a different node to the server, and with no access to the server database.

As tasks are running, they may post ‘in progress’ updates to the celery result backend. To pull those updates into the server database (and make them visible to users), we have a periodic background task which poll results from celery and updates them into the server DB.

This worked well for a while, but as the scale of jobs increased, so did the time taken to perform the refresh operation.

As an example, we had a job of ~280K tasks, which took in excess of 3 hours to refresh. This is less than the time taken for the job to complete, but it does mean we don’t get timely updates - it appears to users as if the job is ‘stuck’, not progressing.

Optimisation

The logic goes like this: each time the refresh operation runs, some number of tasks will be newly completed, call it n. This number is on the order of 1-10 task per second. So if the refresh runs once a second, we’re refreshing +100K tasks, of which only ~10 (0.01%) have changed state.

This is clearly inefficient.

So what if instead we pick out a batch of, say, 1,000 tasks to refresh each time? That seems like it wouldn’t work - if we take 1,000 tasks out of a pool of 100K, what are the odds that any of them will change state?

Maths

Lets define some variables. Tasks can be divided into 3 overlapping states

U: Unknown state, the task may be pending, it may have run and just not be refreshed yetC: Completed, the ran to completion and was refreshedR: Ran, but hasn’t been refreshed yet (these tasks also belong toU)

So if we have U tasks of unknown state, and we take one at random, the probability it is in state R is R/U. If we take a sample k of tasks, then the number we expect to update to completed is k*R/U.

So in each refresh, we expect the number of complete tasks to increase as

C' = k * R(t) / U(t)

The (t) is because these are functions which vary over time

What are R and U?

Well U is the total number of tasks N minus the number of tasks which are completed C

U(t) = N - C(t)

R is the number of tasks which have run up to that point, minus the number of those which have been marked as completed. If we assume a constant task throughput as previously mentioned (n)

R(t) = n*t - C(t)

Combining these 3 equations, we get

C' = k * (n*t - C)/(N - C)

What now?

Well, the refresh is operation complete when all the tasks have run and been refreshed - that is, when C(t) = N

Substituting that into the above equation and doing a little algebraic slight of hand, we get

t = N / n

which is the time at which we expect the refresh operation to complete.

Interpretation

The above result is interesting for two reasons.

First, notice that it doesn’t depend on k, the sample size. In other words, even if we take a bigger random sample to refresh at each step, the operation will still take the same amount of time to complete.

Second, if we consider the extreme case - where we refresh every task each time - n tasks complete at each refresh and all n of them will be marked as completed. So the time to complete would be total number of tasks divided by n -> t = N / n

The exact same as random sampling!

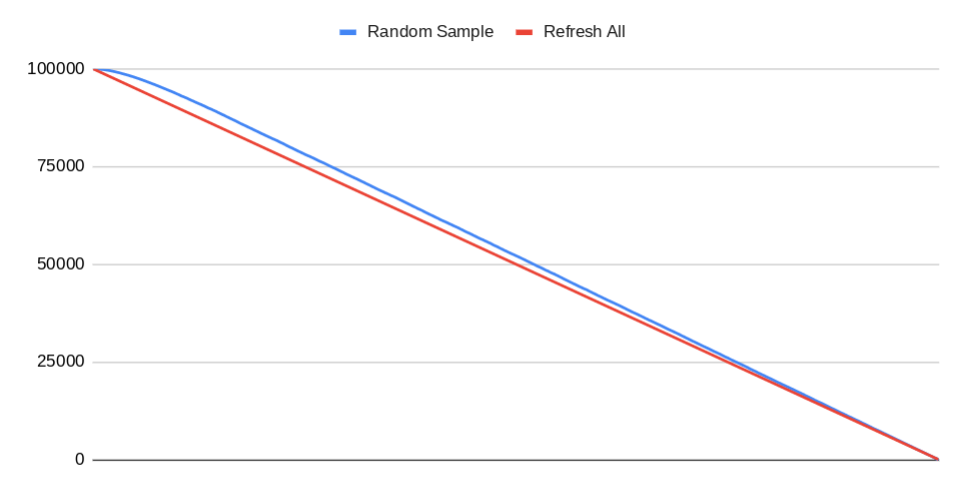

This feels wrong. And yet, a simulation shows it to be true.

The above graph shows the number of tasks in unknown state U over time. Initial population N=100,000, job run rate n=40, and random sample size k=1,000

Sure, the random sampling is slower to update progress at the start. But as the number of tasks waiting to be update (in state R) accumulates, the hit rate for random sampling increases, ultimately converging on the same completion time as refreshing all.

And going back to the original problem, refreshing 1,000 tasks is significantly faster than refreshing +100K, which gives us more frequent updates. So in a practical sense, the random sampling may actually report progress faster than refreshing all!

Conclusion

Honestly, the random sampling felt like a hacky workaround.

The fact that it works as well as refreshing all - proved, mathematically - is nuts and pretty damn cool.

We are working on a replacement for our ‘job engine’, which may make all this moot. But for a stopgap, it’ll do for me.

Also, apologies for the code-block equations. I can’t figure how to get mathjax working 😕

Chris.

[zero division? never heard of her]