A Data Structure for Pokemon Cards

28 May 2022Spring cleaning

Around this time of year, I get an urge to clean out my room, get rid of junk, old books and DVDs. One thing I did this year was to throw out all the boxes from wardrobe: the boxes for old technologies — laptops, phones — some things I don’t even own anymore.

Anyway. In clearing out my wardrobe, I rediscovered my Pokemon cards.

Well, more accurately, I always knew where they were. They were just hard to get at, buried under all those boxes.

A wild problem appeared

My old Pokemon cards were in a ring binder, filled with card display sheets — nine slots per page, double sided (18 total).

Now, every Pokemon has a number, and I want to arrange my Pokemon cards in numerical order.

The most simple arrangement is to assign one slot for each Pokemon. This what I had done when I put my cards away roughly 20 years ago. Of course, back then, that was a much more reasonable proposition; there were only 151 Pokemon.

Now there are almost 1,000!

For that I would need around 55 display sheets, not impossible, but probably a tight fit (granted, I could buy a second binder). But more to the point, there are going to be A LOT of empty slots. Surprisingly, of the original 151, I was only missing one Pokemon: Nidoking.

And what I’ve ignored up to this point is variants — there can be multiple, different cards for the same Pokemon. I even have some different versions of the same card: shiny and non-shiny, English and Japanese (and a couple French for some reason).

For my 150, I had just crammed all the variants into a single slot. But I want to see my cards. So ideally I want each variant to get its own slot.

What I’ve described above — one slot per Pokemon — is like a fix-length array, the sort of thing you have in C. This works fine if you have a fixed number of items, if all (or most) of the slots will be filled, and if you have the storage capacity to allocate all those slots.

(Putting variants into the same slot is like having an array of stacks, but lets not complicate things).

Everything changed when the booster attacked

Okay, so forget one slot-per-Pokemon. The simplest thing is to just put the cards into the album, in order, without gaps. Easy-peasy.

But then, in a bout of nostalgia, I bought some booster packs.

I want to put these new cards in the album, but I want to maintain the numerical order. So I have to insert a new card in the correct slot, and move everything after it along one slot.

What if I get a new Bulbasaur variant (Pokemon #1)?

Then I’d have to move every one of my hundreds of cards along one slot. That would be a massive, tedious hassle.

In computer science, if we wanted efficient inserts while maintaining order, we might use something like a linked list, or a binary tree, or such like. But those structures don’t really map to our album of pages of slots.

We could do like a database — insert the cards in arbitrary order, and keep an index of where each one is. But that’s not really what we’re going for; we want to be able to browser the cards in order. An ordered scan of an index would involve a lot of jumping around.

With our desired arrangement, inserting a new card is always going to require moving things around (unless the new card happens to go in the very end of the album). All we can do is try to minimise the number of ‘move operations’.

Paging

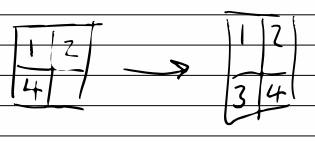

How about this: when we want to insert a new card, first insert an empty page after the page where we want to insert the card. Insert the card, and move everything along one, overflowing onto the newly inserted, empty page. With this, we do, at most, 18 moves per insert.

Actually, lets refine that slightly. If we do multiple inserts, we don’t want to be inserting pages willy-nilly.

So lets say, if the page we want to insert into (or the one after) has a free slot, insert the new card and move everything along as appropriate. Otherwise, insert a new page.

Another tweak is, if the card is inserted on the first side of the page, insert the new page in front instead of behind.

This method reduces the number of moves significantly, but could lead to lots of empty slots and pages that contain only one card. Not ideal.

But perhaps we can have some ‘compaction’ process — that is, if I find myself bored on a Sunday afternoon, I can move all the cards up to eliminate the empty slots.

(Anyone who had a Windows PC in the 90s will likely be familiar with defragmenting).

Can we do better?

Divide and conquer

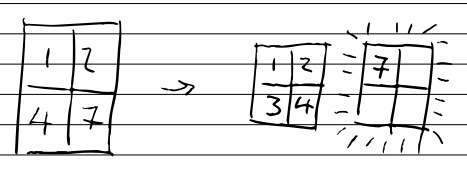

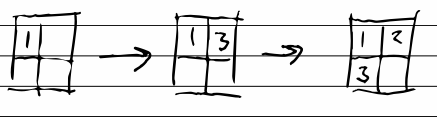

In the previous scheme, we insert a page and move the cards down one slot, leading to a page with a single card. What if, instead, we insert a new page, and move half of the cards to the new page. Then, insert the new one and move around as necessary.

As before, we have a maximum of 18 moves per insert, but now every page is at least half full. This, I think, is much more aesthetically pleasing.

And as before, we can do compaction as necessary.

Swiss cheese

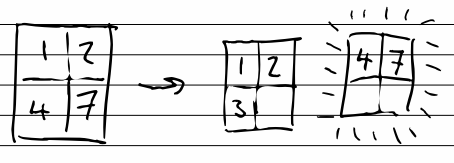

What about this — instead of putting a card in every slot, we put a card in every other slot.

Half of the time (ish) we can just insert a card without moving anything. If the slot we want to put the card in is occupied, we move things up; and because of the defuse arrangement of cards, we won’t have to do much moving up until we hit any empty slot.

And if a single page gets (too) full, we just insert a new page, and spread that full page out into it.

This, again, is more aesthetically pleasing than a mostly empty page.

What’s the average moves per insert? Answers on the back of a postcard.

Of course, the main drawback is that the album is, on average, 50% full. Which isn’t very efficient.

Placement

Up to this point, I’ve assumed that if there are multiple free slots that I card could go in, I would choose the first.

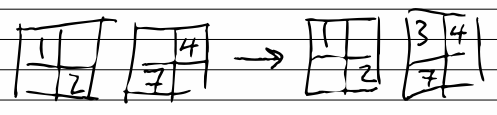

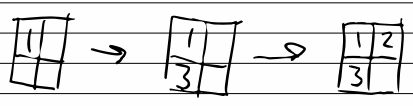

For example, if we have 1, E, E, E, 5 and want to insert 3, we would probably put it in the first available slot - 1, 3, E, E, 5

But if we later want to add 2, now we have to move the 3 we already placed.

So an improvement to this would be to instead place the 3 in the second empty slot - 1, E, 3, E, 5 - then when we come to insert 2, we don’t have to move anything.

In real life, the cards aren’t likely to be so evenly spaced out, but we can at least place the card at a relative position, i.e. 3 goes roughly half way between 1 and 5.

Possible downside to this approach is it will tend to scatter the cards, which may look messy. On the other hand, it may look better to have them more evenly spaced.

It’s also possible that it would require more moves when compacting.

Algorithm, I choose you!

The approach I ultimately went with was insert-and-divide.

I don’t have any evidence to support this being the superior technique. It just feels best. I’m tempted to do some simulations to put some actual numbers one it (watch this space…)

In any case, it seems to work well enough. Tho one thing I didn’t anticipate was how hard it is to open and close the binder rings.

Chris.

[the diagrams are only 4 slots because I’m lazy, okay]